Description of Procedure or Service

Policy Description

Arthropod vectors, including mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, and mites, that feed on vertebrate hosts can spread bacteria, protozoa, and viruses during feeding to their susceptible host, resulting in a variety of infections and diseases. Arboviruses (Arthropod-borne viruses) include Zika virus, West Nile virus (WNV), chikungunya virus, dengue virus (DENV), yellow fever virus (YFV), and Colorado tick fever virus (CTF) to name a few. Malaria and babesiosis are both conditions caused by arthropod-borne protozoan parasites, Plasmodium and Babesia, respectively. Conditions caused by arthropod-borne bacteria include rickettsial diseases, ehrlichiosis, anaplasmosis, and Lyme disease as well as other Borrelia-associated disorders (Calisher, 1994; CDC, 2018). Isolation, identification, and characterization of these various infections depend on the causative agent. Identification methods may include culture testing, microscopy, and staining techniques; moreover, molecular testing, such as nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), and serologic testing, including immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) assays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), can be used for laboratory diagnosis (Miller et al., 2018)

For Lyme disease and testing for Borrelia burgdorferi, please see AHS-G2143 Lyme Disease. For Zika virus testing, please see AHS-G2133 Zika Virus Risk Assessment.

Scientific Background

Hematophagous arthropods, such as mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, and mites, can spread opportunistic bacteria, protozoa, and viruses to host organisms when feeding. Numerous outbreaks of arthropod-borne disease have been documented, including plague, an acute febrile disease caused by Yersinia pestis through the bite of infected fleas, which resulted in more than 50 million deaths in Europe alone during the “Black Death” outbreak. More than 3000 cases of plague were reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) between 2010 and 2015 with 584 deaths. Today, most cases of plague occur in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar, and Peru (WHO, 2017).

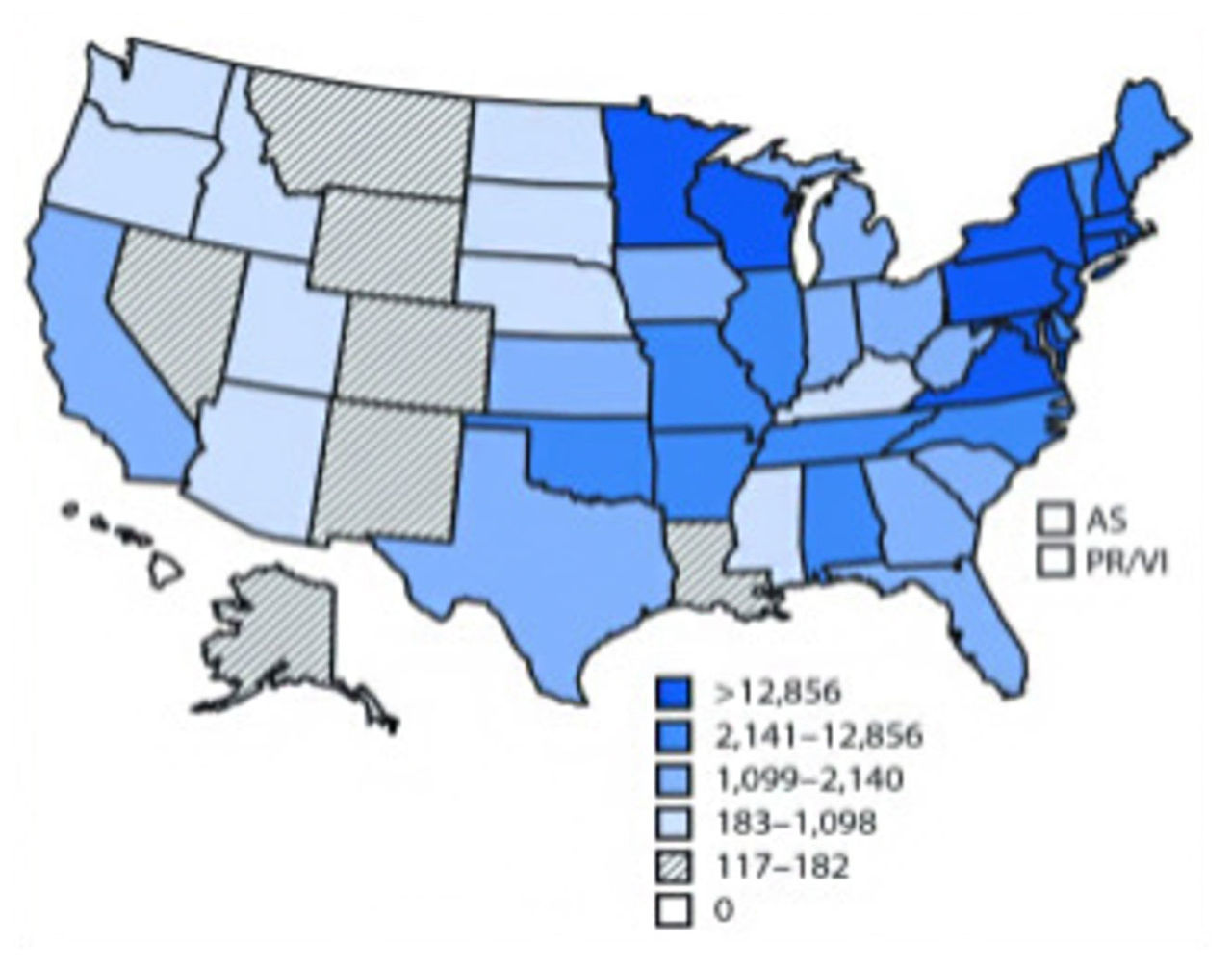

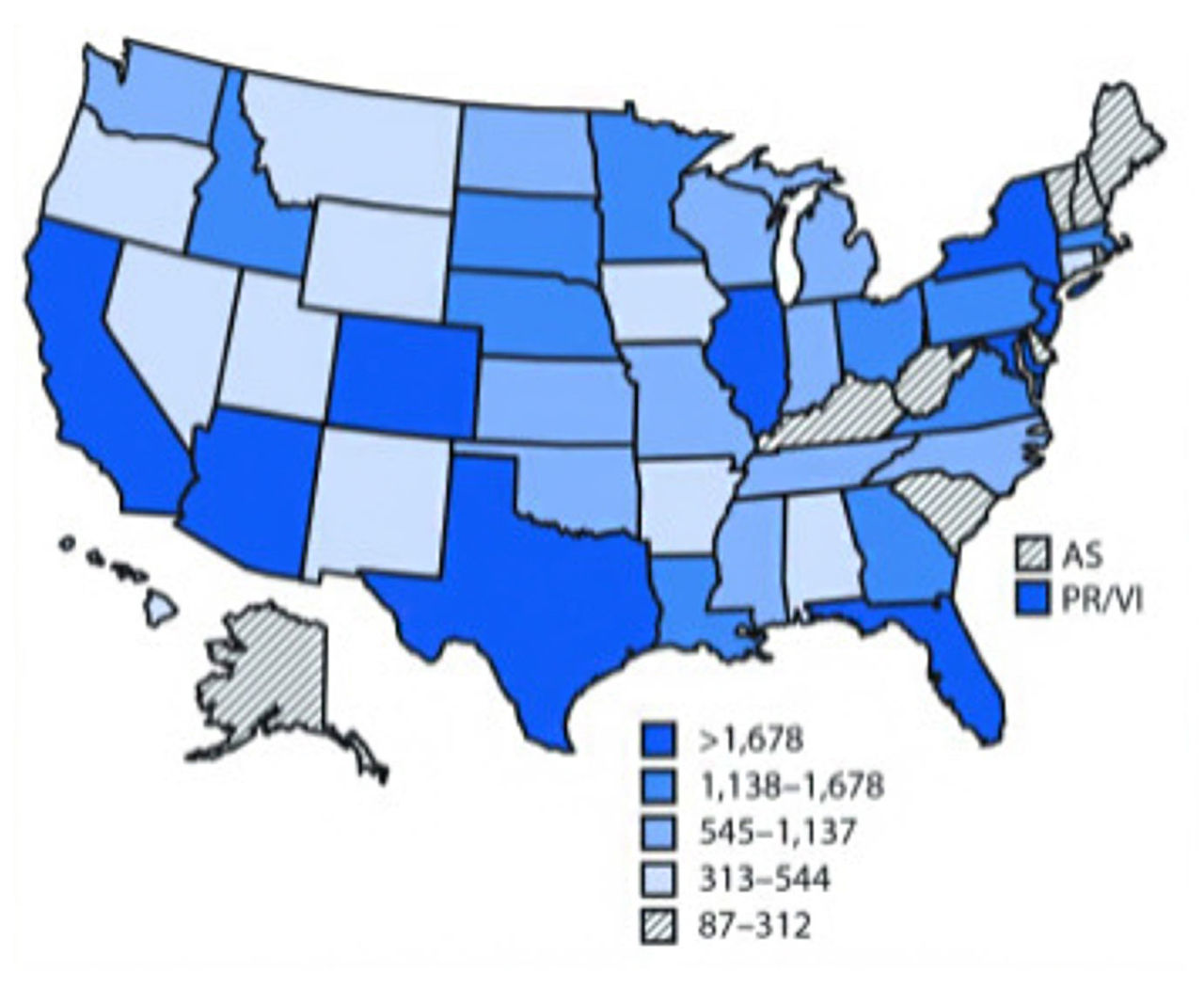

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a large increase in the number of vector-borne diseases within the United States and its territories between 2004-2016. More than 640,000 cases were reported during that time; in fact, infections of tick-borne bacteria and protozoa more than doubled during that time frame. “In the United States, 16 vectorborne diseases are reportable to state and territorial health departments, which are encouraged to report them to the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS). Among the diseases on the list that are caused by indigenous pathogens are Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi); West Nile, dengue and Zika virus diseases; plague (Yersinia pestis); and spotted fever rickettsioses (e.g., Rickettsia rickettsii). Malaria and yellow fever are no longer transmitted in the United States but have the potential to be reintroduced (Rosenberg et al., 2018).” New vector-borne infections are emerging; for example, two unknown, life-threatening RNA viruses spread by ticks have been identified in the U.S. since 2004. Although both tick- and mosquito-borne diseases are increasing across the U.S., the CDC reports that these two vectors are showing different trends. The mosquito-borne diseases are characterized by epidemics; for example, West Nile Virus is essentially limited to the continental U.S. but spread rapidly since its introduction to New York in 1999 whereas chikungunya and dengue primarily occur within the U.S. territories. On the other hand, the tick-borne disease increase occurs in the continental U.S. and has been a gradual, steady rate increase with Lyme disease comprising 82% of all tick-borne diseases (Rosenberg et al., 2018).

This figure shows the number of tick-borne diseases in the US states and territories reported to the CDC, 2004-2016 (Rosenberg et al., 2018)

This figure shows the number of mosquito-borne diseases in the US states and territories reported to the CDC, 2004-2016 (Rosenberg et al., 2018)

Rickettsial infections

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is the most common rickettsial infection in the U.S. with 2553 cases reported to the CDC alone in 2008. RMSF is caused by Rickettsia rickettsia, spread in the U.S. predominantly by Dermacentor variabilis the American dog tick) and D. andersoni (the Rocky Mountain wood tick), and can be found throughout North America as well as parts of South America. The Council for State and Territorial Epidemiologists combined RMSF with other rickettsial diseases into the more broad “spotted fever rickettsiosis” designation in 2009. Besides the obligatory tick bite, typical symptoms of RMSF include fever, headache, and rash with the characteristic rash occurring in approximately 90% of patients within five days of illness. If left untreated, RMSF can be fatal but can easily be treated with antimicrobial therapy upon timely diagnosis. Definitive diagnosis of RMSF cannot usually be made via culture because Rickettsia cannot be grown in cell-free culture media since they are obligate intracellular bacteria requiring living host cells. RMSF diagnosis can be made via either skin biopsy prior to treatment with antibiotics or through serologic testing using indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFAs). IgG antibodies are more specific than IgM antibodies since the latter can give false-positive results due to cross-reactivity with other bacterial pathogens. A drawback of IFA is that usually it is unreliable for the first five days of infection until antibody levels are high enough for detection. The CDC and major clinical labs do offer a PCR-based assay for RMSF (Sexton & McClain, 2018).

Since 2001, thirteen other human rickettsiae belonging to the spotted fever group (SFG) have been identified. All SFGs can cause fever, headache, and myalgia and are arthropod-borne (primarily ticks and mites). Most patients with an SFG display a rash and/or a localized eschar. Rickettsialpox, caused by R. akari, is transmitted from the bite of a house mouse mite, typically after mouse extermination programs result in a decrease of the mite’s food supply. It is typically a relatively mild disease that can resolve itself without treatment within three weeks, but treatment hastens improvement. Rickettsiosis can also be due to infection with R. parkeri, R. amblyommii, and Rickettsia species 364D (also called R. philipii). Isolation of SFG rickettsiae is rare in clinical practice due to the difficulty of obtaining culture; consequently, serology, immunologic detection from tissue, and PCR are more often used for diagnosis. Microimmunofluorescent (MIF) antibody tests, ELISA, and Western blot immunoassays can be used to detect convalescent IgG and IgM antibodies, but these methods can only be used at least 10-14 days after the onset of illness when antibody concentrations are high enough for detection. PCR is a very specific technique. PCR using tissue samples has higher specificity than whole blood PCR. Immunologic detection from a tissue biopsy requires the use of special laboratory equipment so it is not as frequently used as either the serologic or PCR detection methods (Sexton & McClain, 2017).

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis

Human ehrlichiosis was first reported in 1986, and the causative agent for human granulocytic anaplasmosis, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, was identified in 1994. Both ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are transmitted from the bite of infected ticks and have similar clinical and laboratory manifestations. Ehrlichiosis can be caused by Ehrlichia chaffeensis, E. ewingii, and E. muris. Typically, patients have a fever within an incubation period of one to two weeks. Other symptoms can include malaise, myalgia, headache, chills, gastrointestinal distress, and cough. Both leukopenia and thrombocytopenia can occur. Diagnosis via culture is extremely difficult. “Until 1995, only two isolates of E. chaffeensis had been recovered from humans; in both cases, this process required over 30 days of cultivation. The isolation of A. phagocytophilum from three additional patients has been accomplished using a cell culture system derived from human promyelocytic leukemia cells (Sexton & McClain, 2016). IFA testing for bacteria-specific antibodies is the most common method for diagnosing ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis, but similar to rickettsiae, ELISA, PCR, and immunochemical tissue staining can be used as well. Unlike rickettsiosis, ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis can also be detected by the presence of characteristic intraleukocytic morulae in a peripheral blood smear or buffy coat smear (Sexton & McClain, 2016).

Borrelia Infections

Besides Lyme disease, caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia can cause relapsing fever. Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) in North America is primarily caused by B. hermsii, B. turicatae, B. parkeri, B. miyamotoi, and B. mazzottii, and louse-borne relapsing fever (LBRF) is an infection by B. recurrentis (Barbour, 2018; Miller et al., 2018). The characteristic feature of these infections is the relapsing fever due to cyclical spirochetemia caused by antigenic variation of the spirochetes. Each bout of fever lasts 3 to 12 days with temperatures ranged from 39◦C to 43◦C. Visual analysis by Giemsa or Wright staining blood smears taken during a febrile episode is common practice. PCR can also be on a variety of samples, including CSF, blood, tissue, or even culture medium. Culture and serologic testing are not typically performed on the Borrelia that cause TBRF and LBRF due to the lack of facilities that grow these cultures and to cross-reactivity to other antibodies. One exception is using antibodies to the GlpQ protein characteristic of these Borrelia species but not to B. burgdorferi (Lyme disease) (Barbour, 2018).

Protozoa infections

Babesiosis is due to primarily Babesia microti in the U.S, but B. divergens and B. venatorum are the primary causative agents of babesiosis in Europe and China, respectively. The incubation period of Babesia depends on the mode of transfection: 1-4 weeks following a tick bite or up to 9 weeks following a blood transfusion even though incubation periods up to six months have been reported. The most common symptoms of infection include a fever, fatigue, malaise, chills, sweats, headache, and myalgia. Immunocompromised individuals can develop relapsing babesiosis due to an absent or impaired production of antibodies with approximately 20% mortality rate for patients who develop relapsing babesiosis. A majority of patients with babesiosis are also co-infected with other tick-borne bacterial pathogens. “Preferred tools for diagnosis of babesiosis include blood smear for identification of Babesia organisms and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for detection of Babesia DNA. Serology can be a useful adjunct to blood smear and PCR (Krause & Vannier, 2017).” Serology is not ideal in diagnosing an acute infection since antibody concentrations remain elevated post-recovery.

Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, and P. ovale are responsible for malaria. They are spread by the bite of an Anopheles mosquito where their sporozoites infect the liver within one to two hours. Within the hepatocyte, they form merozoites. Upon rupturing into the bloodstream, the merozoites infect red blood cells for trophozoite formation, causing the erythrocytic stage of the life cycle where additional merozoites are released. During this stage of the cycle, the symptoms of malaria, including fever, occur. This process usually takes 12 to 35 days, but clinical manifestations can be delayed in individuals with partial immunity or those who are taking ineffective prophylaxis (Breman, 2018). Other initial symptoms can include irregular heartbeat, cough, anorexia, gastrointestinal distress, sweating, chills, malaise, arthralgia, and myalgia. Malaria, if left untreated, can also include acidosis, hypoglycemia, severe anemia, renal and hepatic impairment, and edema. It can be fatal. Parasite-based diagnosis can include microscopic examination of blood smears, which can often identify the species of Plasmodium as well as the parasite density, and antigen-based tests. Rapid diagnostic testing (RDT) of the antigens using immunochromatographic methods is available, but the accuracy of the RDT can vary considerably. NAATs can also be used to identify a malarial infection, and NAATs “are typically used as a gold standard in efficacy studies for antimalarial drugs, vaccines, and evaluation of other diagnostic agents” with a “theoretical limit of detection for PCR…estimated at 0.02 to 1 parasite/microL (Hopkins, 2018).”

Viral infections

Examples of arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) include West Nile virus (WNV), dengue, yellow fever virus (YFV), chikungunya, and Colorado tick fever virus to name a few. In the United States, WNV is the most common arbovirus reported to the CDC. In 2016, 96% of the reported 2,240 cases of domestic arboviruses were WNV with 61% of the WNV cases reported being neuroinvasive. Neuroinvasive WNV includes meningitis, encephalitis, and acute flaccid paralysis (Burakoff, Lehman, Fischer, Staples, & Lindsey, 2018). In general, most infected individuals are asymptomatic with only 20-40% of infected patients showing any characteristic symptoms of WNV, including fever, headache, malaise, myalgia, anorexia, and rash. Diagnosis of WNV of a symptomatic individual usually occurs with a WNV IgM antibody capture ELISA (MAC-ELISA) assay. A patient with symptoms of a neurologic infection does require a lumbar puncture. Confirmatory testing can include a plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT). PCR testing is primarily used with immunocompromised patients who have delayed or absent antibody production, patients with a history of prior flavivirus infections, and blood donors who may be asymptomatic (L. Petersen, 2018).

Dengue virus (DENV) infection is a result of being bitten by an infected Aedes aegypti or A. albopictus mosquito. Four distinct DENV types of Flavivirus are known: DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV3, and DENV-4. DENV is endemic throughout much of the tropical regions of the world, but the only region of the U.S. endemic for DENV is Puerto Rico. The last major outbreak occurred in Puerto Rico in 2010 where 26,766 cases of suspected DENV were reported and 47% of all laboratory tested specimen were positive (CDC, 2013, 2014). “Dengue fever…is an acute febrile illness defined by the presence of fever and two or more of the following but not meeting the case definition of dengue hemorrhagic fever: headache, retro-orbital or ocular pain, myalgia and/or bone pain, arthralgia, rash, hemorrhagic manifestations…[and] leukopenia. The cardinal feature of dengue hemorrhagic fever is plasma leakage due to increased vascular permeability as evidenced by hemoconcentration (≥20 percent rise in hematocrit above baseline), pleural effusion, or ascites [4]. DHF is also characterized by fever, thrombocytopenia, and hemorrhagic manifestations…. (Thomas, Rothman, Srikiatkhachorn, & Kalayanarooj, 2018)”. Laboratory diagnostic testing includes direct detection of viral components in serum or indirect serologic assays. “Detection of viral nucleic acid or viral antigen has high specificity but is more labor intensive and costly; serology has lower specificity but is more accessible and less costly (Thomas et al., 2018).” Culture testing as a diagnostic tool usually is time-prohibitive.

Colorado tick fever virus (CTFV) is a Reoviridae transmitted primarily by the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni) in the western US and Canada. Transmission of CTFV has also been reported in blood transfusions. The incubation period can last up to 14 days, and symptoms include fever, headache, chills, myalgia, leukopenia, and prostration. Only 15% of symptomatic patients demonstrate a rash. Serologic tests are usually not helpful until at least 10-14 days for antibody production whereas RT-PCR can be used on the first day of symptoms (L. R. Petersen, 2017).

Yellow fever, occurring primarily in sub-Saharan Africa and South America, is a flavivirus spread by mosquitoes that causes hemorrhagic fever with a high fatality rate. An outbreak in Brazil in January–March 2018 resulted in 4 of 10 patients infected with YFV dying. None of those showing symptoms had been vaccinated against YFV. Yellow fever causes hemorrhagic diathesis due to decreased synthesis of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors as well as hepatic dysfunction, renal failure, and coagulopathy. Yellow fever diagnosis is typically made by a serologic test using an ELISA-IgM assay; however, this assay does cross-react with other flaviviruses and with the YFV vaccination. Rapid diagnostic testing using either PCR or immunoassay is available. Viral isolation and culture can be performed, but it requires inoculation of mosquitoes or mammalian cell culture. Tissue biopsy, such as liver, cannot be performed on the living patient due to possible fatal hemorrhaging; biopsy would be performed during the post-mortem workup (Monath, 2018).

Chikungunya virus, endemic in many tropical and subtropical regions of the world, is transmitted by the mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Within the U.S., chikungunya is prevalent in Puerto Rico where approximately 25% of blood donors were seropositive; it has also bene reported in Florida. Both dengue and Zika are transmitted by the same vectors, so these viruses often co-circulate in a given geographic area. Chikungunya can cause acute febrile polyarthralgia and arthritis. The predominant testing method for diagnosis of chikungunya is the detection of viral RNA via either RTPCR or virus serology using either ELISA or IFA. Viral culture is typically not used as a diagnostic tool but is used for epidemiologic research (Wilson & Lenschow, 2018).

Types of Testing

| Test | Description | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Culture | Culture growth depends on the pathogen being studied. If the pathogen is an obligate intracellular organism, then it must be isolated using more sophisticated cell culture techniques. In many circumstances, culture is used for research and/or epidemiology rather than as a diagnostic tool (Biggs et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2018). | At times, culture testing is not as sensitive as either NAAT or serologic testing and can be time-intensive when treatment should not be delayed. Depending on the organism, this may require high biosafety level laboratory for culture growth (Biggs et al., 2016). |

| Indirect immunofluorescene antibody (IFA) assays | IFA is a serologic assay that can be used to test for the presence of antibodies, such as IgG and IgM, reactive against the pathogen (Biggs et al., 2016). | Depending on the pathogen, IFA can be a useful tool. At times, though, it can cross-react with either a prior vaccination or infection (Monath, 2018). An acute infection can often be determined by performing IFA in both the acute phase and convalescent phase where at least a fourfold increase in antibodies is indicative of an acute infection (Biggs et al., 2016). |

| Darkfield microscopy | Darkfield microscopy can be used to detect the presence of microorganisms, such as motile spirochetes (Miller et al., 2018). | This technique is not widely available, and transport of sample must be done immediately if testing of motile specimen is desired (Miller et al., 2018). |

| Blood-smear microscopy | Blood-smear microscopy can be either thick or thin and is typically performed on a sample stained with an eosinazure-type dye, such as Giemsa, to look at intracellular structures or morphological features (Biggs et al., 2016). | This technique should be performed by an experienced microscopist since it can be inconsistent. As compared to other techniques, this technique is relatively inexpensive (Biggs et al., 2016). |

| Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) | NAATs can include polymerase chain reaction (PCR), real-time PCR (RTPCR), or other enzymedependent amplification testing for the presence of nucleic acids (DNA or RNA). | NAATs can be specific and sensitive; however, they may not be available at all laboratories and/or can be costly. Some NAATs are available as rapid diagnostic tools. NAATs have been used on serum, whole blood, tissue, CSF, and even formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsies from autopsy tissues. The sensitivity of the technique can vary depending on the sample; for example, whole blood PCR for R. rickettsii is less sensitive than a similar sample test for E. chaffeensis (Biggs et al., 2016). |

Analytical Validity

The use of antibodies to detect and diagnose arthropod-associated infections and diseases is a common practice. Johnson et al. in 2000 first reported the use of monoclonal antibody-based capture ELISA testing for a variety of alphaviruses, including chikungunya, flaviviruses, including dengue and yellow fever, and bunyaviruses. They concluded, “IgG ELISA results correlated with those of the standard plaque-reduction neutralization assays. As expected, some test cross-reactivity was encountered within the individual genera, and tests were interpreted within the context of these reactions. The tests were standardized for laboratory diagnosis of arboviral infections, with the intent that they be used in tandem with the corresponding IgM antibody-capture ELISAs (Johnson, Martin, Karabatsos, & Roehrig, 2000).” Kalish and associates also demonstrated that IgG and/or IgM antibody responses can still occur up to 20 years post-infection; consequently, a rise in antibody titer does not necessarily indicate a current, acute infection (Kalish et al., 2001).

Clinical Validity

In 2013, Kato and colleagues tested the sensitivity of two different RT-PCR-based assays for Rickettsia—PanR8, an assay that tests for Rickettsia in general, and RRi6, an assay specific for R. rickettsii. Both of these methods were more sensitive in testing for Rickettsia than the nested PCR method of the CDC; moreover, both of these methods are faster than the nested PCR method (1 hr versus 1-2 days, respectively) (Kato et al., 2013). These results were corroborated in 2014 by Denison and colleagues. They used a multiplex PCR assay to correctly identify all cell controls for R. rickettsii, R. parkeri, and R. akari; moreover, no false-positive results were reported using this methodology. “This multiplex real-time PCR demonstrates greater sensitivity than nested PCR assays in FFPE [formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded] tissues and provides an effective method to specifically identify cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever, rickettsialpox, and R. parkeri rickettsiosis by using skin biopsy specimens (Denison, Amin, Nicholson, & Paddock, 2014).”

The FDA has approved the use of the BinaxNOW malaria test for screening and diagnosing malaria. Even though, this testing method is considerably faster than other methods (as low as 1.1-1.7 hours complete turnaround time (Ota-Sullivan & Blecker-Shelly, 2013)), the use of BinaxNOW in nonendemic areas is a point of controversy due to relatively low sensitivity (84.2%) and for misclassifying Plasmodium falciparum malaria as non-falciparum (Dimaio, Pereira, George, & Banaei, 2012). Moreover, it has been reported that Salmonella typhi can give a false-positive for malaria using the BinaxNOW test (Meatherall, Preston, & Pillai, 2014).

State and Federal Regulations, as applicable

On 6/29/2017, the FDA approved the Rickettsia Real-Time PCR Assay (K170940) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) with the following definition: “An in vitro diagnostic test for the detection of Rickettsia spp. nucleic acids in specimens from individuals with signs or symptoms of rickettsial infection and epidemiological risk factors consistent with potential exposure. Test results are used in conjunction with other diagnostic assays and clinical observations to aid in the diagnosis infection, in accordance with criteria defined by the appropriate public health authorities in the Federal government (FDA, 2018).”

On 9/1/2009, the FDA approved the BinaxNOW Malaria Positive Control Kit (K083744) rapid diagnostic test (RDT), an in vitro qualitative immunochromatographic assay, for use by hospital and commercial laboratories, but it is not approved for individual or physician offices (Arguin & Tan, 2017; FDA, 2018).

As of 8/7/2018, the FDA has approved the following assays for the detection of West Nile Virus (FDA, 2018): West Nile Virus ELISA IgG model EL0300G and West Nile Virus IgM Capture ELISA model EL0300M by Focus Technologies, Inc., West Nile Virus IgM Capture ELISA model E-WNV02M and West Nile Virus IgG Indirect ELISA by Panbio Limited, West Nile Detect IgM ELISA by Inbios Intl, Inc., Spectral West Nile Virus IgM Status Test by Spectral Diagnostics, Inc., and the EUROIMMUN Anti-West Nile Virus ELISA (IgG) and EUROIMMUN Anti-West Nile Virus ELISA (IgM) by Euroimmun US, Inc.

Additionally, many labs have developed specific tests that they must validate and perform in house. These laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) are regulated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) as high-complexity tests under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA ’88). As an LDT, the U. S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved or cleared this test; however, FDA clearance or approval is not currently required for clinical use.

***Note: This Medical Policy is complex and technical. For questions concerning the technical language and/or specific clinical indications for its use, please consult your physician.

Policy

BCBSNC will provide coverage for testing for mosquito or tick-related infections when it is determined to be medically necessary because the medical criteria and guidelines noted below are met.

Benefits Application

This medical policy relates only to the services or supplies described herein. Please refer to the Member's Benefit Booklet for availability of benefits. Member's benefits may vary according to benefit design; therefore member benefit language should be reviewed before applying the terms of this medical policy.

When testing for mosquito or tick-related infections is covered

- Concerning suspected cases of rickettsial diseases (see signs and symptoms below), including Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis, Rickettsia species 364D rickettsiosis, Rickettsia spp (mild spotted fever), and R. akari (rickettsialpox):

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) assay for IgG antibodies

- A limit of one unit of IFA assay meets coverage criteria.

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of ehrlichiosis and/or anaplasmosis (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- NAAT, including PCR, of whole blood; AND

- Indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) assay for IgG antibodies; AND

- Microscopy for morulae detection

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) caused by Borrelia hermsii, B. parkerii, B. mazzottii, or B. turicatae (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Dark-field microscopy of peripheral blood smear; OR

- Microscopy of Wright- or Giemsa-stained blood smear

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of babesiosis (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Giemsa- or Wright-stain of blood smear

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of malaria (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Smear microscopy to diagnose malaria, determine the species of Plasmodium, identify the parasitic life-cycle stage, and/or quantify the parasitemia

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of chikungunya virus (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Viral culture for diagnosis; OR

- NAAT, including PCR, for presence of chikungunya in serum sample; OR

- Indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) assay for IgM antibodies during both the acute and convalescent phases

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of West Nile Virus (WNV) (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- IFA for WNV-specific IgM or IgG antibodies in either serum or CSF; AND

- Plaque reduction neutralization test for WNV

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of Yellow Fever Virus (YFV) (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Plaque reduction neutralization test for YFV; AND

- NAAT, including PCR, for YFV; AND

- Serologic assays to detect virus-specific IgM and IgG antibodies

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of Dengue virus (DENV) (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Plaque reduction neutralization test for DENV; AND

- NAAT, including PCR, for DENV; OR

- IgM antibody capture ELISA (MAC-ELISA); OR iv. NS1 ELISA

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of Colorado Tick Fever (CTF) (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered medically necessary:

- Virus-specific IFA-stained blood smears; OR

- IFA for CTF-specific antibodies

- The following is considered medically necessary:

When testing for mosquito or tick-related infections is not covered

- Concerning suspected cases of rickettsial diseases (see signs and symptoms below), including Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis, Rickettsia species 364D rickettsiosis, Rickettsia spp (mild spotted fever), and R. akari (rickettsialpox):

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- Standard blood culture; OR

- Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), including PCR; OR

- IFA assay for IgM antibodies;

- More than one unit of IFA testing

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of ehrlichiosis and/or anaplasmosis (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- IFA assay for IgM antibodies; OR

- Standard blood culture

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) caused by Borrelia hermsii, B. parkerii, B. mazzottii, or B. turicatae (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- IFA assay for either IgG or IgM for Borrelia; OR

- Culture testing for Borrelia

- The following is considered to be investigational: i. NAAT, including PCR

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of babesiosis (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- IFA assay for either Babesia IgG or IgM; OR

- NAAT, including PCR

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of malaria (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- NAAT, including PCR

- IFA for Plasmodium antibodies

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of West Nile Virus (WNV) (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- NAAT, including PCR, for WNV

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- Concerning suspected cases of Dengue virus (DENV) (see signs and symptoms below):

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

- IgG-ELISA

- Hemagglutination testing

- The following is considered not medically necessary:

Policy Guidelines

- Typical signs and symptoms of rickettsial diseases usually begin 3 – 12 days after initial bite and can include (Biggs et al., 2016):

- Fever

- Headache

- Chills

- Malaise

- Myalgia

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Photophobia

- Anorexia

- Skin rash

- Ulcerative lesion with regional lymphadenopathy (for Rickettsia species 364D rickettsiosis)

- Typical signs and symptoms of ehrlichiosis and/or anaplasmosis usually begin 5-14 days after an infected tick bite, and they include (Biggs et al., 2016):

- Fever

- Headache

- Malaise

- Myalgia

- Shaking chills

- Gastrointestinal issues, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, in ehrlichiosis

- Typical signs and symptoms of tick-borne relapsing fever include (CDC, 2015c):

- Recurring febrile episodes that last approximately 3 days separated by approximately 7 days

- Nonspecific symptoms that occur in at least 50% of cases include headache, myalgia, chills, nausea, arthralgia, and vomiting

- Typical signs and symptoms of babesiosis can include (CDC, 2012):

- Hemolytic anemia

- Splenomegaly

- Hepatomegaly

- Jaundice

- Nonspecific flu-like symptoms such as fever, chills, body aches, weakness, and fatigue

- Typical signs and symptoms of malaria can include (Arguin & Tan, 2017):

- Fever

- Influenza-like symptoms such as chills, headache, body aches, and so on

- Anemia

- Jaundice

- Seizures

- Mental confusion

- Kidney failure

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Typical signs and symptoms of chikungunya include (Staples et al., 2017):

- High fever (>102◦F or 39◦C)

- Joint pains (usually multiple joints, bilateral, and symmetric)

- Headache

- Myalgia

- Arthritis

- Conjunctivitis

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Maculopapular rash

- Typical signs and symptoms of WNV include (Nasci et al., 2013):

- Headache

- Myalgia

- Arthralgia

- Gastrointestinal symptoms

- Maculopapular rash

- Less than 1% develop neuroinvasive WNV with symptoms of meningitis, encephalitis, or acute flaccid paralysis

- Typical signs and symptoms of yellow fever include (Gershman & Staples, 2017):

- Nonspecific influenzalike syndrome including fever, chills, headache, backache, myalgia, prostration, nausea, and vomiting in initial illness

- Toxic form of disease symptoms include jaundice, hemorrhagic symptoms, and multisystem organ failure

- Typical signs and symptoms of dengue can include (CDC, 2014):

- Fever

- Headache

- Retro-orbital eye pain

- Myalgia

- Arthralgia

- Erythematous maculopapular rash

- Petechiae

- Leukopenia

- Typical signs and symptoms of CTF can include (CDC, 2015a):

- Fever

- Chills

- Headache

- Myalgia

- Malaise

- Sore throat

- Vomiting

- Abdominal Pain

- Maculopapular or petechial rash

Note: For Lyme disease and testing for Borrelia burgdorferi, please see AHS-G2143 Lyme Disease. For Zika virus testing, please see AHS-G2133 Zika Virus Risk Assessment.

Guidelines and Recommendations

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Diagnosis and Management of Tickborne Rickettsial Diseases (Biggs et al., 2016): In 2016, the CDC released their guidelines and recommendations concerning Rickettsial diseases, including Rocky Mountain spotted fever, in the MMWR. The table below summarizes their recommended diagnostic tests for tickborne rickettsial diseases:

Table 4. Recommended diagnostic tests for tickborne rickettsial diseases

| Disease | Whole blood (PCR) | Eschar biopsy or swab (PCR) | Rash biopsy (PCR) | Microscopy for morulae detection | IFA assay for IgG antibodies (acute and convalescent)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever | Yesⴕ | − | Yes | − | Yes |

| Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis | − | Yes | Yes | − | Yes |

| Rickettsia species 364D rickettsiosis | − | Yes | − | − | Yes |

| Ehrlichia chaffeensis ehrlichiosis (human monocytic ehrlichiosis) | Yes | − | − | Yes | Yes |

| Ehrlichia ewingii ehrlichiosis | Yes | − | − | Yes | Yes |

| Ehrlichia muris-like agent ehrlichiosis | Yes | − | − | − | Yes |

| Human anaplasmosis (human granulocytic anaplasmosis) | Yes | − | − | Yes | Yes |

Abbreviations: IFA = indirect immunofluorescence antibody; IgG = immunoglobulin G; PCR = polymerase chain reaction.

*IFA assay is insensitive during the first week of illness; a sample should be collected during this interval (acute specimen), and a second sample should be collected 2-4 weeks later (convalescent specimen) for comparison. Elevated titers alone are not sufficient to diagnose infection with tickborne rickettsial diseases; serial titters are needed for confirmation. Demonstration of at least a fourfold rise in antibody titer is considered confirmatory evidence of acute infection.

ⴕPCR of whole blood samples for Rickettsia rickettsii has low sensitivity; sensitivity increases in patients with severe disease.

To summarize their recommendations, even though indirect immunofluorescence antibody assays (IFAs) are insensitive typically during the first week of an acute infection, they are the standard reference for tickborne rickettsial infections and that a minimum of two tests are to be performed for diagnosis. Usually, one sample is taken early after the initial symptoms are present, and a second sample is taken 2-4 weeks later. A minimum of a fourfold rise in antibody titer is required to confirm diagnosis. In cases of ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis, during the first week, PCR amplification can be used on whole blood for diagnosis, but PCR has low sensitivity in Rocky Mountain spotted fever except in patients with severe disease. Morulae detection via either blood-smear or buffy-coat preparation microscopy can also be indicative of ehrlichiosis or anaplasmosis. “Rickettsiae cannot be isolated with standard blood culture techniques because they are obligate intracellular pathogens; specialized cell culture methods are required. Because of limitations in availability and facilities, culture is not often used as a routine confirmatory diagnostic method for tickborne rickettsial diseases (Biggs et al., 2016).”

Tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) (CDC, 2015c): In the U.S., TBRF can be caused by Borrelia hermsii, B.. parkerii, and B. turicatae with B. hermsii being the most common causative agent. Due to the relapsing nature of TBRF (usually ~3 days per febrile episode followed by an afebrile period of approximately one week), the CDC recommends testing during a febrile episode since spirochetemia is at its highest (100- 1000 times higher than even early cases of Lyme disease). “The definitive diagnosis of TBRF may be based on the observation of relapsing fever spirochetes (Borrelia hermsii, B. turicatae, or B. parkerii in the US) in peripheral blood smears of a symptomatic person by a microscopist trained in spirochete identification. Although best visualized by dark field microscopy, the organisms can also be detected using Wright-Giemsa or acridine orange stains… Although not valuable for making an immediate diagnosis, serologic testing is available through public health laboratories and some private laboratories. Acute serum should be taken within 7 days of symptom onset and convalescent serum should be taken at least 21 days after symptoms start. Early antibiotic treatment may blunt the antibody response and the antibody levels may wane quickly during the months after exposure. To confirm the diagnosis of TBRF, Borrelia specific antibody titers should increase 4-fold between acute and convalescent serum samples, and convalescent serum antibody levels should be at least two standard deviations above pooled negative controls. Serologic testing for TBRF is not standardized and results may vary by laboratory. Patients with TBRF may have false-positive tests for Lyme disease because of the similarity of proteins between the two organisms. Incidental laboratory findings include normal to increased white blood cell count with a left shift towards immature cells, a mildly increased serum bilirubin level, mild to moderate thrombocytopenia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and slightly prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) (CDC, 2015c).”

Colorado Tick Fever (CTF) (CDC, 2015b): As of 2015, CTF was reportable in Arizona, Colorado, Montana, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming. “Laboratory diagnosis of CTF is generally accomplished by testing of serum to detect viral RNA or virus-specific immunoglobulin (Ig) M and neutralizing antibodies. Antibody production can be delayed with CTF, so tests that measure antibodies may not be positive for 14– 21 days after the onset of symptoms. RT-PCR (reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction) is a more sensitive test early in the course of disease. CTF testing is available at some commercial and state health department laboratories and at CDC. Contact your state or local health department for assistance with diagnostic testing. They can help you determine if samples should be sent to the CDC Arbovirus Diagnostic Laboratory for further testing (CDC, 2015b).”

Babesiosis (CDC, 2012): According to the CDC website, the most recent update about babesiosis for health professionals is from 2012 (with revision in 2013). Diagnosis can be challenging due to the nonspecific clinical manifestations of the disease. “For acutely ill patients, the findings on routine laboratory testing frequently include hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia. Additional findings may include proteinuria, hemoglobinuria, and elevated levels of liver enzymes, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine. If the diagnosis of babesiosis is being considered, manual (non-automated) review of blood smears should be requested explicitly. In symptomatic patients with acute infection, Babesia parasites typically can be detected by light-microscopic examination of blood smears, although multiple smears may need to be examined. Sometimes it can be difficult to distinguish between Babesia and Plasmodium (especially P. falciparum) parasites and even between parasites and artifacts (such as stain or platelet debris). Consider having a reference laboratory confirm the diagnosis—by blood-smear examination and, if indicated, by other means, such as molecular and/or serologic methods tailored to the setting/species (CDC, 2012).”

Malaria (Arguin & Tan, 2017): The CDC considers smear microscopy as the gold standard in diagnosing malaria since it can determine the species, identify the stage of parasitic life-cycle, and quantify the parasitemia; however, microscopy should be performed within a few hours due to the timeliness of diagnosis and treatment of disease. “It is an unacceptable practice to send these tests to an offsite laboratory or batch them for results to be provided days later.” In the event that microscopy is unavailable, rapid immunochromatographic diagnostic tests (RDTs) that typically use a dipstick or cassette can be used, but RDTs cannot usually distinguish between the different pathogenic species and are less sensitive than either microscopy or PCR. “In addition, CDC recommends that positive and negative RDT results always be confirmed by microscopy in US health care settings… PCR tests are also available for detecting malaria parasites. Although these tests are more sensitive than routine microscopy, results are not usually available as quickly as microscopy results should be, thus limiting the utility of this test for acute diagnosis. PCR testing is most useful for definitively identifying the species of malaria parasite and detecting mixed infections. Species confirmation by PCR is available at the CDC malaria laboratory (Arguin & Tan, 2017).”

Chikungunya (Staples, Hills, & Powers, 2017): In the CDC Yellow Book, concerning the chikungunya virus, they recommend that “the differential diagnosis of chikungunya virus infection depends on the clinical signs and symptoms as well as where the person was suspected of being infected.” The other diseases to consider include: Zika, malaria, leptospirosis, parvovirus, group A Streptococcus, rubella, measles, dengue, enterovirus, adenovirus, alphavirus infections, post-infectious arthritis, and rheumatic conditions. Laboratory diagnosis is done by serum testing for detection of virus, viral nucleic acids, or virus-specific IgM and neutralizing antibodies. “During the first week after onset of symptoms, chikungunya can often be diagnosed by performing viral culture or nucleic acid amplification on serum. Virus-specific IgM and neutralizing antibodies normally develop toward the end of the first week of illness. Therefore, to definitively rule out the diagnosis, convalescent-phase samples should be obtained from patients whose acute-phase samples test negative. Testing for chikungunya virus is performed at CDC, several state health department laboratories, and several commercial laboratories (Staples et al., 2017).”

West Nile Virus (WNV) (Nasci et al., 2013): “WNV infections are most frequently confirmed by detection of anti-WNV immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibodies in serum or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The presence of anti-WNV IgM is usually good evidence of recent WNV infection, but may indicate infection with another closely related flavivirus (e.g., St. Louis encephalitis). Because anti-WNV IgM can persist in some patients for >1 year, a positive test result occasionally may reflect past infection unrelated to current disease manifestations. Serum collected within 8 days of illness onset may lack detectable IgM, and the test should be repeated on a convalescent-phase sample. IgG antibody generally is detectable shortly after the appearance of IgM and persists for years. Plaque-reduction neutralization tests (PRNT) can be performed to measure specific virus-neutralizing antibodies. A fourfold or greater rise in neutralizing antibody titer between acute- and convalescent-phase serum specimens collected 2 to 3 weeks apart may be used to confirm recent WNV infection and to discriminate between cross-reacting antibodies from closely related flaviviruses.” NAAT may not be suitable in most cases since the concentrations of WNV RNA are so low by the time a patient begins to show symptoms of infection; however, NAAT may be suitable in immunocompromised individuals who have either delayed or absent antibody development.

Yellow Fever Virus (YFV) (Gershman & Staples, 2017): Isolation of the virus or NAAT should be performed as early as possible in suspected cases of YFV. “However, by the time more overt symptoms are recognized, the virus or viral RNA might be undetectable. Therefore, virus isolation and nucleic acid amplification should not be used to rule out a diagnosis of yellow fever… Serologic assays to detect virus-specific IgM and IgG antibodies (sic). Because of cross-reactivity between antibodies raised against other flaviviruses, more specific antibody testing, such as a plaque reduction neutralization test, should be done to confirm the infection (Gershman & Staples, 2017).” Since YFV is a nationally notifiable disease, clinicians should contact their state and/or local health departments according to their respective local, state, and/or federal guidelines.

Dengue (CDC, 2017): Diagnosis of dengue can be via isolation of virus, serological tests such as immunoassays, and molecular methods, including RT-PCR. The CDC’s testing algorithm for dengue is as follows:

- PCR—PCR of serum sample within first 5 days of symptom can detect DENV usually with 80- 90% sensitivity; however, a negative test result in the first five days should be corroborated by serological testing after the 5th day of illness.

- MAC-ELISA (IgM antibody capture ELISA)—even though this testing is limited due to cross reactivity with other flaviviruses, it is “the most commonly employed in diagnostic laboratories” and is commercially available.

- IgG-ELISA—this method can be used to determine past dengue infection or used to monitor rise in titer between the acute and convalescent phases of a dengue infection. The two tests should be performed at least seven days apart.

- NS1 ELISA—The non-structural protein 1 (NS1) of dengue can be used to diagnose an acute infection between 1 and 18 days post onset of symptoms. “The NS1 assay may also be useful for differential diagnostics between flaviviruses because of the specificity of the assay.”

- PRNT (Plaque Reduction and Neutralization Test)—PRNT can be used as a serological specificity tool in convalescent sera by measuring the titer of the neutralizing antibodies to determine the level of protective antibodies. “The assay is a biological assay based on the principle of interaction of virus and antibody resulting in inactivation of virus such that it is no longer able to infect and replicate in cell culture. Some of the variability of this assay is differences in interpretation of the results because of the cell lines and virus seeds used as well as the dilution of the sera.” A high throughput version of the PRNT that utilizes a colorimetric assay is called microneutralization PRNT.

2018 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM) (Miller et al., 2018)

Laboratory Diagnosis of Tick-borne Infections: The information given below outlines the diagnostic procedures for tick-borne infections and is taken from Table 47 of the 2018 IDSA/ASM guidelines.

Bacteria

| Etiologic Agents | Diagnostic Procedures | Optimum Specimens |

|---|---|---|

| Relapsing fever borreliae Borrelia hermsii (western US) Borrelia parkeri (western US) Borrelia turicatae (southwestern US) Borrelia mazzottii (southern US) | Primary test: Darkfield microscopy or Wright, Giemsa, or Diff-Quik stains of peripheral thin or/ and thick blood smears. Can be seen in direct wet preparation of blood in some cases. Other testing: NAAT, Culture, Serologic testing | Blood or bone marrow for the primary test. Blood or body fluids for NAAT. Serum for culture or serologic testing. |

| Borrelia miyamotoi (B. miyamotoi infection, hard tick-borne relapsing fever) | Primary test: NAAT Serology: EIA for detection of antibodies to recombinant GlpQ antigen | Blood for NAAT and serum for serology. |

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum (human granulocytotropic anaplasmosis) | Primary test: NAAT Alternate Primary (if NAAT is unavailable): Wright or Giemsa stain of peripheral blood or buffy coat leukocytes during week first week of infection. Serology: Acute and convalescent IFA titers for IgG-class antibodies to A. phagocytophilum antibodies Immunohistochemical staining of Anaplasma antigens in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens | Blood for both NAAT and Wright or Giemsa stain

Serum for Serology

Bone marrow biopsies or autopsy tissues (spleen, lymph nodes, liver, and lung) for IHC staining |

| Ehrlichia chaffeensis (human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis) Ehrlichia muris Ehrlichia ewingii | Primary test: NAAT (Only definitive diagnostic assay for E. ewingii) Wright or Giemsa stain of peripheral blood or buffy coat leukocytes smear during first week of infection Serology: acute and convalescent IFA titers for Ehrlichia IgG-class antibodies Immunohistochemical staining of Ehrlichia antigens in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens | Whole blood for NAAT

Blood for Wright or Giemsa stain

Serum for serology

Bone marrow biopsies or autopsy tissues (spleen, lymph nodes, liver and lung) for IHC staining |

| Rickettsia rickettsii (RMSF) Other spotted fever group Rickettsia spp (mild spotted fever) R. typhi (murine typhus) R. akari (rickettsialpox) R. prowazekii (epidemic typhus) | Serology: acute and convalescent IFA for Rickettsia sp IgM and IgG antibodies NAAT Immunohistochemical staining of spotted fever group rickettsiae antigens (up to first 24 h after antibiotic therapy initiated) in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens | Serum for serology

Skin biopsy (preferably a maculopapule containing petechiae or the margin of an eschar) or autopsy tissues (liver, spleen, lung, heart, and brain) for NAAT Skin biopsy (preferably a maculopapule containing petechiae or the margin of an eschar) or autopsy tissues (liver, spleen, lung, heart, and brain) for IHC staining |

Protozoa

| Etiologic Agents | Diagnostic Procedures | Optimum Specimens |

|---|---|---|

Babesia microti Babesia spp | Primary test: Giemsa, Wright, Wright-Giemsa stains of peripheral thin and thick blood smears (Giemsa preferred) Primary test for acute infection: NAAT Serology: acute and convalescent IFA titers for Babesia IgG-class antibodies NOTE: Not recommended for acute infection. | Whole blood (EDTA vacutainer tube is a second choice) for staining Blood for NAAT and serum for serology |

Virus

| Etiologic Agents | Diagnostic Procedures | Optimum Specimens |

|---|---|---|

| Colorado tick fever virus | Virus-specific IFA-stained blood smears Serology: IFA titers or complement fixation | Blood Serum |

| Powassan/deer tick virus | Primary test: IgM capture EIA (available only through state departments of public health) NAAT | Serum for EIA Blood, CSF, brain (biopsy or autopsy) for NAAT |

The IDSA/ASM does note that most PCR-based assays for babesiosis only detect B. microti even though there are at least three other species of Babesia that can cause the infection. “Real time PCR available from CDC and reference labs… Serology does not distinguish between acute and past infection (Miller et al., 2018).”

Their recommendation for the main diagnostic testing for malaria due to Plasmodium falciparum, P. ovale, P. vivax, P. malariae, and P. knowlesi is “Stat microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained thick and thin blood films (repeat testing every 12–24 h for a total of 3 exams before ruling out malaria); rapid antigen detection tests followed by confirmatory blood films within 12–24 h.” They make the following special remark: “Antigen tests lack sensitivity with low parasitemia and non-falciparum malaria and do not differentiate all species. PCR from some reference laboratories will detect and differentiate all species. Calculation of percentage parasitemia (using thick or thin blood films) is required for determining patient management and following response to therapy (Miller et al., 2018).” Concerning dengue virus DENV, “Plaque reduction neutralization tests (PRNTs) are considered the reference standard for detection of antibodies to arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) and provide improved specificity over commercial serologic assays; however, due to the complexity of testing, PRNT is currently only available at select public health laboratories and the CDC.” They note that false-positives for antibodies to DENV may not necessarily indicate DENV infection since it can also be indicative of a prior flavivirus infection, such as West Nile virus or Zika virus. They do state the following concerning the use of NAAT, “Detection of DENV RNA by NAAT is preferred for acutely ill patients. Recently, detection of the DENV NS1 antigen, which is secreted from infected host cells as early as 1 day after symptom onset and up to 10 days thereafter, has become an acceptable alternative to NAAT for diagnosis of acute DENV infection (Miller et al., 2018).”

For West Nile Virus (WNV), they state: “Laboratory diagnosis of WNV, and most other arboviruses, is typically accomplished by detecting virus-specific IgM- and/or IgG-class antibodies in serum and/or CSF.” Possible false-positives can occur if a patient has been vaccinated against yellow fever or if they have had a previous infection of another flavivirus. They do note that WNV RNA detection via NAAT can be performed on either the serum or CSF for immunosuppressed patients.

American Academy of Pediatrics 2018 Redbook

Babesiosis (AAP, 2018a): “Acute, symptomatic cases of babesiosis typically are diagnosed by microscopic identification of Babesia parasites on Giemsa- or Wright-stained blood smears… PCR assay is particularly recommended for use in early infection, when parasites are more difficult to visualize on blood smear. However, PCR assay should be used with caution when monitoring response to therapy, because B. microti can be detected for weeks and months after parasites no longer are visualized on blood smear.” They do state that antibody testing can be useful in distinguishing between Babesia and Plasmodium infections whenever blood smear examinations and travel histories are inconclusive or for detecting individuals with very low levels of parasitemia.

Non-Lyme Borrelia Infections (AAP, 2018b): Dark-field microscopy and Wright-, Giemsa-, or acridine orange-stained preparations of blood smears can be used to observe the presence of spirochetes in the initial febrile episode, but their presence is more difficult to determine in future recurrences. Both enzyme immunoassay and Western immunoblot analysis can detect serum antibodies; however, “these antibody tests are not standardized and are affected by antigenic variations among and within Borrelia species and strains.” As of publication, PCR and antibody-based testing were still under development and were not widely available.

Ehrlichia, Anaplasma, and Related Infections (AAP, 2018e): PCR testing should be performed within the first week of illness to diagnose anaplasmosis, ehrlichiosis, and other Anaplasmataceae infections because doxycycline treatment rapidly decreases the sensitivity of PCR. Consequently, negative PCR results do not necessarily indicate a lack of infection. Occasionally, Giemsa- or Wright staining of blood smears can be performed to identify the presence of the morulae of Anaplasma in the first week of illness. Culture testing for isolation is not performed. “Immunoglobulin (Ig) M serologic assays are prone to false-positive reactions, and IgM… can remain elevated for lengthy periods of time, reducing its diagnostic utility. Serologic testing may be used to demonstrate a fourfold change in IgG-specific antibody titer by indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) assay between paired acute and convalescent specimens taken 2 to 4 weeks apart.”

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) (AAP, 2018h): “The gold standard for serologic diagnosis of RMSF is the indirect immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) test. A negative serologic test result from the acute phase does not rule out a diagnosis of RMSF in any case… A fourfold or greater increase in antigen-specific IgG between acute and convalescent sera obtained 2 to 4 weeks apart confirms the diagnosis (6 weeks for convalescent serum for Rickettsia africae).”

Rickettsialpox (AAP, 2018g): Rickettsialpox can be mistaken for other rickettsial infections. Ideally, the use of R. akari-specific antigen is recommended for serologic diagnosis, but it has limited availability. Otherwise, indirect IFA for R. rickettsia, the causative agent of RMSF, since R. akari has extensive cross-reactivity. Again, a demonstration of at least a fourfold increase in antibody titers taken 2-6 weeks apart is indicative of infection.

Chikungunya (AAP, 2018c): “Laboratory diagnosis generally is accompanied by testing serum to detect virus, viral nucleic acid, or virus-specific immunoglobulin (Ig) M and neutralizing antibodies.” RTPCR can be used to diagnose chikungunya during the first week after onset of symptoms since chikungunya-specific antibodies have not formed at that time. After the first week, serum testing of IgM or a plaque-reduction neutralization test can be performed.

Dengue (AAP, 2018d): “Dengue virus is detectable by RT-PCR or NS1 antigen EIAs from the beginning of the febrile phase until day 7 to 10 after illness onset.” Cross-reactivity occurs between anti-dengue virus IgM and other flaviviruses, including Zika. IgG EIA and hemagglutination testing is not specific for diagnosis of dengue, and IgG antibodies remain elevated for life; consequently, a fourfold increase in IgG between the acute and convalescent phase can confirm recent infection. “Reference testing is available from the Dengue Branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.”

Malaria (AAP, 2018f): Microscopic identification of Plasmodium on both thick and thin blood films should be performed. “If initial blood smears test negative for Plasmodium species but malaria remains a possibility, the smear should be repeated every 12 to 24 hours during a 72-hour period… Serologic testing generally is not helpful, except in epidemiologic surveys… Species confirmation and antimalarial drug resistance testing are available free of charge at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for all cases of malaria diagnosed in the United States.” One FDA-approved RADT is available in the U.S. to hospitals and commercial labs; however, both positive and negative test results must be corroborated by microscopic examination.

West Nile Virus (WNV) (AAP, 2018i): PCR is not recommended for diagnosis of WNV in immunocompetent patients since WNV RNA is usually no longer detectable by the initial onset of symptoms. “Detection of anti-WNV immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibodies in serum or CSF is the most common way to diagnose WNV infection.” Anti-WNV IgM levels can remain elevated for longer than 1 year so a positive test result may be indicative of a prior infection. “Plaque-reduction neutralization tests can be performed to measure virus-specific neutralizing antibodies and to discriminate between cross-reacting antibodies from closely related flaviviruses. A fourfold or greater increase in virus-specific neutralizing antibodies between acute-and convalescent-phase serum specimens collected 2 o 3 weeks apart may be used to confirm recent WNV infection.”

International Encephalitis Consortium (IEC) (Venkatesan et al., 2013)

In 2013, the IEC released their Case Definitions, Diagnostic Algorithms, and Priorities in Encephalitis. Concerning arboviruses, they state the following: “For most arboviruses, serologic testing of serum and CSF is preferred to molecular testing, since the peak of viremia typically occurs prior to symptom onset. For example, in patients with West Nile virus (WNV) associated with neuroinvasive disease, CSF PCR is relatively insensitive (57%) compared with detection of WNV IgM in CSF. The cumulative percentage of seropositive patients increases by approximately 10% per day during the first week of illness suggesting the need for repeat testing if the suspicion for disease is strong in those with initially negative results. Notably, arbovirus IgM antibodies may be persistently detectable in the serum and, less commonly, in the CSF, for many months after acute infection, and therefore may not be indicative of a current infection. Therefore, if possible, documentation of acute infection by seroconversion and/or 4-fold or greater rises in titre using paired sera is recommended (Venkatesan et al., 2013).”

Billing/Coding/Physician Documentation Information

This policy may apply to the following codes. Inclusion of a code in this section does not guarantee that it will be reimbursed. For further information on reimbursement guidelines, please see Administrative Policies on the Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina web site at www.bcbsnc.com. They are listed in the Category Search on the Medical Policy search page.

| Code | PA required | PA Not Required | Not Covered |

|---|---|---|---|

| 86757 | X | ||

| 87040 | X | ||

| 87798 | X | ||

| 86280 | X | ||

| 86753 | X | ||

| 86784 | X | ||

| 86666 | X | ||

| 88346 | X | ||

| 88350 | |||

| 86790 | X | ||

| 86619 | X | ||

| 85060 | X | ||

| 87207 | X | ||

| 87254 | X | ||

| 86750 | X | ||

| 86753 | X | ||

| 86788 | X | ||

| 86789 | X | ||

| 86790 | X | ||

| 87449 | X | ||

| 87899 | X |

Scientific Background and Reference Sources

AAP, A. A. o. P. (2018a). Babesiosis. In D. Kimberlin, M. Brady, M. Jackson, & S. Long (Eds.), Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (pp. 235-237): American Academy of Pediatrics.

AAP, A. A. o. P. (2018b). Borrelia Infections Other Than Lyme Disease. In D. Kimberlin, M. Brady, M. Jackson, & S. Long (Eds.), Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (pp. 252-255): American Academy of Pediatrics.

AAP, A. A. o. P. (2018c). Chikungunya. In D. Kimberlin, M. Brady, M. Jackson, & S. Long (Eds.), Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (pp. 271-272): American Academy of Pediatrics.

AAP, A. A. o. P. (2018d). Dengue. In D. Kimberlin, M. Brady, M. Jackson, & S. Long (Eds.), Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (pp. 317-319): American Academy of Pediatrics.

AAP, A. A. o. P. (2018e). Ehrlichia, Anaplasma, and Related Infections. In D. Kimberlin, M. Brady, M. Jackson, & S. Long (Eds.), Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (pp. 323-328): American Academy of Pediatrics.

AAP, A. A. o. P. (2018f). Malaria. In D. Kimberlin, M. Brady, M. Jackson, & S. Long (Eds.), Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (pp. 527-537): American Academy of Pediatrics.

AAP, A. A. o. P. (2018g). Rickettsialpox. In D. Kimberlin, M. Brady, M. Jackson, & S. Long (Eds.), Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (pp. 696-697): American Academy of Pediatrics.

AAP, A. A. o. P. (2018h). Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. In D. Kimberlin, M. Brady, M. Jackson, & S. Long (Eds.), Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (pp. 697-700): American Academy of Pediatrics.

AAP, A. A. o. P. (2018i). West Nile Virus. In D. Kimberlin, M. Brady, M. Jackson, & S. Long (Eds.), Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (pp. 888-891): American Academy of Pediatrics.

Arguin, P., & Tan, K. (2017). Chapter 3 Infectious Diseases Related to Travel: Malaria. In G. Brunette (Ed.), CDC Yellow Book 2018: Health Information for International Travel. New York: Oxford University Press.

Barbour, A. G. (2018, 03/12/2018). Clinical features, diagnosis, and management of relapsing fever. UpToDate.

Biggs, H. M., Behravesh, C. B., Bradley, K. K., Dahlgren, F. S., Drexler, N. A., Dumler, J. S., . . . Traeger, M. S. (2016). Diagnosis and Management of Tickborne Rickettsial Diseases: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Other Spotted Fever Group Rickettsioses, Ehrlichioses, and Anaplasmosis - United States. MMWR Recomm Rep, 65(2), 1-44. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6502a1

Breman, J. G. (2018, 07/24/2018 ). Clinical manifestations of malaria in nonpregnant adults and children. UpToDate.

Burakoff, A., Lehman, J., Fischer, M., Staples, J. E., & Lindsey, N. P. (2018). West Nile Virus and Other Nationally Notifiable Arboviral Diseases - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 67(1), 13-17. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6701a3

Calisher, C. H. (1994). Medically important arboviruses of the United States and Canada. Clin Microbiol Rev, 7(1), 89-116.

CDC. (2012, 07/13/2013). Babesiosis: Resources for Health Professionals.

CDC. (2013, 12/14/2015). Dengue in Puerto Rico.

CDC. (2014, 09/06/2014). Dengue: Clinical Guidance.

CDC. (2015a, 01/13/2015). Colorado Tick Fever Health Care Providers: Clinical & Laboratory Evaluation.

CDC. (2015b, 01/13/2015). Colorado Tick Fever Health Care Providers: Diagnostic Testing.

CDC. (2015c, 01/08/2016). Tick-borne Relapsing Fever (TBRF): Information for Clinicians.

CDC. (2017, 08/03/2017). Dengue: Laboratory Guidance and Diagnostic Testing.

CDC. (2018, 05/17/2018). About the Division of Vector-Borne Diseases.

Denison, A. M., Amin, B. D., Nicholson, W. L., & Paddock, C. D. (2014). Detection of Rickettsia rickettsii, Rickettsia parkeri, and Rickettsia akari in skin biopsy specimens using a multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction assay. Clin Infect Dis, 59(5), 635-642. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu358

Dimaio, M. A., Pereira, I. T., George, T. I., & Banaei, N. (2012). Performance of BinaxNOW for diagnosis of malaria in a U.S. hospital. J Clin Microbiol, 50(9), 2877-2880. doi:10.1128/jcm.01013-12

FDA. (2018). Devices@FDA.

Gershman, M., & Staples, J. (2017). Chapter 3 Infectious Diseases Related to Travel: Yellow Fever. In G. Brunette (Ed.), CDC Yellow Book 2018: Health Information for International Travel. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hopkins, H. (2018, 01/26/2018). Diagnosis of malaria. UpToDate.

Johnson, A. J., Martin, D. A., Karabatsos, N., & Roehrig, J. T. (2000). Detection of anti-arboviral immunoglobulin G by using a monoclonal antibody-based capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol, 38(5), 1827-1831.

Kalish, R. A., McHugh, G., Granquist, J., Shea, B., Ruthazer, R., & Steere, A. C. (2001). Persistence of immunoglobulin M or immunoglobulin G antibody responses to Borrelia burgdorferi 10-20 years after active Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis, 33(6), 780-785. doi:10.1086/322669

Kato, C. Y., Chung, I. H., Robinson, L. K., Austin, A. L., Dasch, G. A., & Massung, R. F. (2013). Assessment of real-time PCR assay for detection of Rickettsia spp. and Rickettsia rickettsii in banked clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol, 51(1), 314-317. doi:10.1128/jcm.01723-12

Krause, P. J., & Vannier, E. G. (2017, 11/13/2017). Babesiosis: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. UpToDate.

Meatherall, B., Preston, K., & Pillai, D. R. (2014). False positive malaria rapid diagnostic test in returning traveler with typhoid fever. BMC Infect Dis, 14, 377. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-377

Miller, J. M., Binnicker, M. J., Campbell, S., Carroll, K. C., Chapin, K. C., Gilligan, P. H., . . . Yao, J. D. (2018). A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiologya. Clinical Infectious Diseases, ciy381-ciy381. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy381

Monath, T. P. (2018, 03/30/2018). Yellow Fever. UpToDate.

Nasci, R., Fischer, M., Lindsey, N., Lanciotti, R., Savage, H., Komar, N., . . . Petersen, L. (2013). West Nile Virus in the United States: Guidelines for Surveillance, Prevention, and Control. Ft. Collins, CO: CDC

Ota-Sullivan, K., & Blecker-Shelly, D. L. (2013). Use of the rapid BinaxNOW malaria test in a 24-hour laboratory associated with accurate detection and decreased malaria testing turnaround times in a pediatric setting where malaria is not endemic. J Clin Microbiol, 51(5), 1567-1569. doi:10.1128/jcm.00293-13

Petersen, L. (2018, 07/30/2018). Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of West Nile virus infection. UpToDate.

Petersen, L. R. (2017, 08/14/2014). Arthropod-borne encephalitides. UpToDate.

Rosenberg, R., Lindsey, N. P., Fischer, M., Gregory, C. J., Hinckley, A. F., Mead, P. S., . . . Petersen, L. R. (2018). Vital Signs: Trends in Reported Vectorborne Disease Cases - United States and Territories, 2004-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 67(17), 496-501. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6717e1

Sexton, D. J., & McClain, M. T. (2016, 08/15/2016). Human ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis. UpToDate.

Sexton, D. J., & McClain, M. T. (2017, 09/12/2018). Other spotted fever group rickettsial infections. UpToDate.

Sexton, D. J., & McClain, M. T. (2018, 05/29/2018). Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. UpToDate.

Staples, J., Hills, S., & Powers, A. (2017). Chapter 3 Infectious Diseases Related to Travel: Chikungunya. In G. Brunette (Ed.), CDC Yellow Book 2018: Health Information for International Travel. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thomas, S., Rothman, A., Srikiatkhachorn, A., & Kalayanarooj, S. (2018, 07/24/2018). Dengue virus infection: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. UpToDate.

Venkatesan, A., Tunkel, A. R., Bloch, K. C., Lauring, A. S., Sejvar, J., Bitnun, A., . . . International Encephalitis, C. (2013). Case definitions, diagnostic algorithms, and priorities in encephalitis: consensus statement of the international encephalitis consortium. Clin Infect Dis, 57(8), 1114-1128. doi:10.1093/cid/cit458

WHO. (2017, 10/31/2017). Plague. News-Room.

Wilson, M. E., & Lenschow, D. J. (2018, 05/07/2018). Chikungunya fever. UpToDate.

Policy Implementation/Update Information

1/1/19 New policy developed. BCBSNC will provide coverage for testing for mosquito or tick-related infections when it is determined to be medically necessary because the medical criteria and guidelines are met. Medical Director review 1/1/2019. Policy noticed 1/1/2019 for effective date 4/1/2019. (sk)

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability in its health programs and activities. Learn more about our non-discrimination policy and no-cost services available to you.

Information in other languages: Español 中文 Tiếng Việt 한국어 Français العَرَبِيَّة Hmoob ру́сский Tagalog ગુજરાતી ភាសាខ្មែរ Deutsch हिन्दी ລາວ 日本語

© 2026 Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina. ®, SM Marks of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, an association of independent Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans. All other marks and names are property of their respective owners. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina is an independent licensee of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association.