Description of Procedure or Service

Definitions

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is an X-linked disorder with variable presentation. FMR1-related disorders include fragile X syndrome, fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS), and FMR1-related primary ovarian insufficiency (POI). Fragile X syndrome occurs in individuals with an FMR1 full mutation or other loss-of-function mutation and is nearly always characterized by moderate intellectual disability in affected males and mild intellectual disability in affected females.

Background

Because FMR1 mutations are complex alterations involving non-classic gene-disrupting alterations (trinucleotide repeat expansion) and abnormal gene methylation, affected individuals occasionally have an atypical presentation with an IQ above 70, the traditional demarcation denoting intellectual disability (previously referred to as mental retardation). Males with an FMR1 full mutation accompanied by aberrant methylation may have a characteristic appearance (large head, long face, prominent forehead and chin, protruding ears), connective tissue findings (joint laxity), and large testes after puberty. Behavioral abnormalities, sometimes including autism spectrum disorder, are common. FXTAS occurs in males (and some females) who have an FMR1 premutation and is characterized by late-onset, progressive cerebellar ataxia and intention tremor. FMR1-related POI (age at cessation of menses <40 years) occurs in approximately 20% of females who have an FMR1 premutation (Saul et al., 2012).

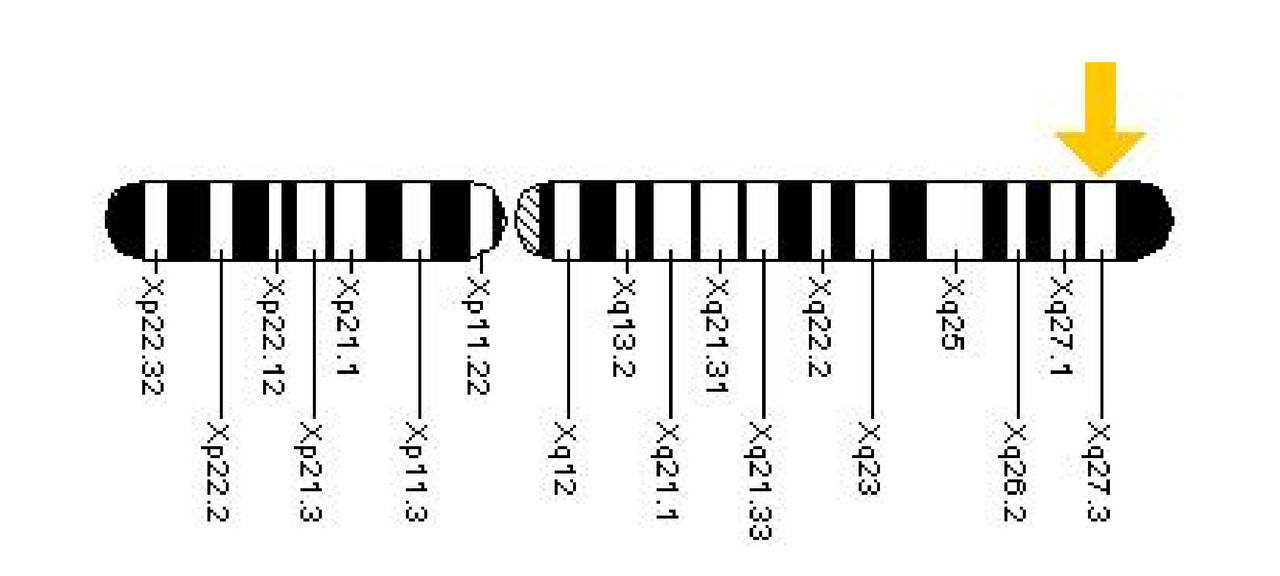

FXS is the most common cause of inherited mental retardation, occurring in approximately 1 in 4,000 males and 1 in 8,000 females, with no apparent increased frequency in particular ethnic groups. It is estimated that up to 3% of children classified with autism spectrum disorder are affected with FXS. The syndrome was first recognized in 1977 when Sutherland linked a fragile site on the X chromosome with the phenotype of X-linked mental retardation and macroorchidism (Sutherland et al., 1977). The FMR1 gene was isolated in 1991 and PCR based testing has since been used to make or confirm the diagnosis of fragile X syndrome. In most cases FXS is caused by a trinucleotide (CGG) repeat expansion in the 5’ untranslated (UTR) region of the gene. Normally, there are fewer than 45 CGG triplet repeats but affected individuals have greater than 200 CGG repeats. These full mutations of the CGG region result in hypermethylation of the promoter region, with subsequent silencing of gene expression and absence of the FMR1 protein (FMRP). (Cleveland Clinic, Accessed Oct 2016).

Clinical symptoms

Fragile X syndrome is a genetic condition that causes a range of developmental problems including learning disabilities and cognitive impairment. Usually, males are more severely affected by this disorder than females.

Affected individuals usually have delayed development of speech and language by age 2. Most males with fragile X syndrome have mild to moderate intellectual disability, while about one-third of affected females are intellectually disabled. Children with fragile X syndrome may also have anxiety and hyperactive behavior such as fidgeting or impulsive actions. They may have attention deficit disorder (ADD), which includes an impaired ability to maintain attention and difficulty focusing on specific tasks. About one-third of individuals with fragile X syndrome have features of autism spectrum disorders that affect communication and social interaction. Seizures occur in about 15 percent of males and about 5 percent of females with fragile X syndrome.

Most males and about half of females with fragile X syndrome have characteristic physical features that become more apparent with age. These features include a long and narrow face, large ears, a prominent jaw and forehead, unusually flexible fingers, flat feet, and in males, enlarged testicles (macroorchidism) after puberty (GHR, Accessed 2016).

Genetics

FXS is caused by loss of function of the FMR1 gene, which results in a deficiency of the Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP). FMRP is a RNA-binding protein normally synthesized in dendrites that controls protein synthesis through inhibition of translation. In the absence of FMRP, it is thought that the excess translation results in over-expression of certain messages and subsequent over-stimulation that cause the FXS phenotype. It has been suggested that RNA toxicity may contribute to the phenotype.

Loss of function of the FMR1 gene is due to expansion of the CGG trinucleotide repeat sequence in the 5’ untranslated region of the gene in 99% of FXS cases. Normally, in unaffected individuals, there are less than 45 CGG repeats. In affected individuals, the CGG repeat sequence has expanded to an excessive number, typically over 200 repeats, with an associated high level of methylation that prevents production of FMRP. The severity of FXS is not predictable by the number of repeats present. All males with the full mutation have mental deficit, but less than 50% of females have cognitive disability. This is thought to be due to variable inactivation of the X chromosome in females.

This expansion of the CGG repeat section of the FMR1 gene occurs through generations. A “premutation” of 55 – 200 CGG repeats is found in women considered to be carriers of FXS. Such carriers are at risk for expansion of the premutation into the “full mutation” number of CGG repeats in their children. It is estimated that 1 in 300 to 1 in 500 females and 1 in 1000 males carry the premutation. The number of repeats present in female premutation carriers is associated with the likelihood of expansion into a full mutation for the next generation. The higher the number of repeats present, the higher the likelihood, with premutations of over 100 repeats carrying a risk of nearly 98% for expansion to a full mutation. Although FXS is an X-linked disorder, inheritance risk is not straightforward due to the incomplete penetrance and variable risk based on the number of repeats. In male carriers, the premutation appears to be stable, and doesn’t expand in subsequent generations.

Typically, CGG repeat premutation carriers are unaffected, although learning difficulties and other milder cognitive presentations have been noted in individuals with repeats over 100. Additionally, presentations not associated with mental deficits have been noted in premutation carriers. These include premature ovarian insufficiency or ovarian failure, which is found in approximately 20% of women with the premutation. Additionally, a late-onset tremor ataxia, known as FXTAS, is seen in 20 – 40% of males with a premutation, and a small percent of female premutation carriers. The penetrance of these disorders in premutation carries is variable, and is not predictable based on the number of repeats.

There is also an intermediate (or gray zone) CGG repeat class, with 45 – 54 repeats. These repeats do not increase the risk for FXS, as they are typically stable. However, expansion of an intermediate repeat to a premutation state has been noted in subsequent generations in a few cases.

Molecular Tests

All general guidelines for Southern blot analysis and PCR in the ACMG Standards and Guidelines for Clinical Genetics Laboratories apply (http://www.acmg.net). The following additional details are specific for fragile X. For this test, there are many valid methods with different strengths and weaknesses. Laboratories will likely need to use more than one method because no single method can characterize all aspects of the FMR1 full mutation, and precision in determining allele size varies between PCR and Southern blot analysis. For mosaic samples spanning the premutation and full mutation ranges, traditional PCR may amplify the premutation population but not the subpopulation with the full mutation. The expected phenotype for an individual with a premutation versus mosaicism for a premutation and full mutation is very different. Therefore, not detecting the full mutation would result in a different risk assessment for fragile X, FXTAS and FXPOI (Sherman et al., 2005). For this reason, the ACMG policy statement recommends that Southern blot analysis always be performed along with traditional PCR, even if a premutation allele is identified by traditional PCR. (Monaghan et al., 2013).

Determination of CGG expansion status is performed by PCR and capillary electrophoresis using the Amplidex FMR1 kit from Asuragen. PCR is performed on DNA isolated from peripheral blood using labeled primers designed to amplify the FMR1 repeat region by triplet repeat primedPCR assay (TP-PCR). PCR products are run on the ABI 3730 Genetic Analyzer to determine the size(s) of the repeat expansion. This TP-PCR assay identified normal to full mutation FMR1 alleles at 100% specificity and 97.4% sensitivity in a previous report.

Based on recommendations of the ACMG Quality Assurance Committee and the Professional Practice and guidelines committee FMR1 CGG repeat size categorized as, Normal <45, Intermediate 45–54, Premutation 55–200, and Full mutation >200.

Thorough interpretation of results is dependent on the indication for testing and relies on good communication of clinical information from the ordering provider. CGG repeats less than 45 are considered normal and are not consistent with a diagnosis of or risk for fragile X syndrome or any of the FMR1-related disorders. Individuals with alleles in the intermediate range of 45-54 CGG repeats would be expected to have a normal phenotype but future generations may be at risk for expansion of the repeat into the premutation or full mutation ranges. Individuals with premutations of 55-200 repeats generally do not have fragile X syndrome but are at risk of other FMR1-associated disorders, POI or FXTAS. Premutation carrier females may have children with fragile X syndrome. Full mutations of greater than 200 CGG repeats are consistent with a diagnosis of fragile X syndrome but are not associated with increased risk of POI or FXTAS. Methylation studies are ordered as a reflex test for samples with premutations and/or full mutations. In cases where the test results are not consistent with the clinical phenotype, additional testing may be required to assess other mutations in FMR1 (Cleveland Clinic, Accessed 2016).

Mosaicism cases involving deleted and full mutation alleles are apparently rare and clinically undistinguishable, but they could be potentially missed by routine FXS testing due to technical limitations. (Goncalves et al., 2016)

Table 1. Summary of Molecular Genetic Testing Used in FMR1-Related Disorders

| Gene | Test Method | Mutations Detected | Mutation Detection Frequency by Test Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| FMR1 | Targeted mutation analysis | PCR. CGG expansion in FMR1 (allele sizes in the normal and lower premutation range) | >99% |

| Southern blot. CGG expansion in FMR1 (all repeat ranges); methylation status | |||

| AGG trinucleotide repeat genotyping. Number and position of AGG trinucleotide repeats that may interrupt the CGG repeats of FMR1 | 100% of alleles of this structure | ||

| Methylation analysis | Methylation of FMR1 promoter region | 100% of alleles with this modification | |

| FISH | Large (partial- or whole-gene) FMR1 deletions | <1% | |

| Deletion/duplication analysis | Large (partial- or whole-gene) FMR1 deletions/duplications | <1% | |

| Sequence analysis | FMR1 sequence variants | <1% |

Source: Saul et al, 2012

Treatment

Early developmental intervention, special education (individual attention, small class size, and avoiding sudden change and excessive stimulation), and vocational training; individualized pharmacologic management of behavioral issues that significantly affect social interaction; routine treatment of medical problems.

FXTAS: supportive care for gait disturbance and/or cognitive deficits. POI: reproductive endocrine evaluation for treatment and counseling for reproductive options. Folic acid should be avoided in individuals with poorly controlled seizures (Saul et al., 2012).

Genetic counseling

All mothers of individuals with an FMR1 full mutation (expansion >200 CGG trinucleotide repeats and abnormal methylation) are carriers of an FMR1 mutation. Mothers and their female relatives who are premutation carriers are at increased risk for FXTAS and POI; those with a full mutation may have findings of fragile X syndrome. All are at increased risk of having offspring with fragile X syndrome, FXTAS, and POI. Males with premutations are at increased risk for FXTAS. Males with FXTAS will transmit their FMR1 premutation expansion to none of their sons and to all of their daughters, who will be premutation carriers. Carrier testing for at-risk relatives and prenatal testing for pregnancies at increased risk are possible if the diagnosis of an FMR1-related disorder has been confirmed in a family member (Gene review, 2012).

Applicable Federal Regulations

N/A

***Note: This Medical Policy is complex and technical. For questions concerning the technical language and/or specific clinical indications for its use, please consult your physician.

Policy

BCBSNC will provide coverage for genetic testing for FMR1 mutations when it is determined to be medically necessary because the medical criteria and guidelines shown below are met.

Benefits Application

This medical policy relates only to the services or supplies described herein. Please refer to the Member's Benefit Booklet for availability of benefits. Member's benefits may vary according to benefit design; therefore member benefit language should be reviewed before applying the terms of this medical policy.

When Genetic Testing for FMR1 Mutations is covered

- Pre- and post-test genetic counseling is recommended for individuals undergoing FMR1 gene testing.

- Diagnostic genetic testing for FMR1 gene CGG repeats and methylation status is considered medically necessary for:

- Males and females with unexplained mental retardation, developmental delay, or autism spectrum disorder, OR

- Symptomatic individuals with features of Fragile X syndrome or a family history of Fragile X syndrome, OR

- Females with unexplained ovarian insufficiency, unexplained ovarian failure, or unexplained elevated FSH prior to age 40, OR

- Individuals with unexplained late-onset tremor-ataxia, OR

- Fetuses of known FMR1 premutation or full mutation carriers

- Carrier screening for FMR1 gene CGG repeat length is considered medically necessary for individuals seeking pre-conception or prenatal care when:

- There is a family history of Fragile X syndrome, OR

- There is a family history of unexplained mental retardation, developmental delay, or autism spectrum disorder, OR

- There is a family history of unexplained late-onset tremor ataxia, OR

- There is a family history of unexplained premature ovarian insufficiency or failure.

When Genetic Testing for FMR1 Mutations is not covered

Determination of FMR1 gene point mutations is considered not medically necessary.

Determination of FMR1 gene deletion is considered not medically necessary.

Population screening for Fragile X syndrome is considered not medically necessary.

Cytogenetic testing for Fragile X syndrome is considered not medically necessary.

Testing for the FMRP protein is considered not medically necessary.

Policy Guidelines

Guidelines and Recommendations

The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommends Fragile X syndrome molecular genetic testing for:

- “Individuals of either sex with mental retardation, developmental delay or autism, especially if they have

- Any physical or behavioral characteristics of fragile X syndrome,

- A family history of fragile X syndrome, or

- Male or female relatives with undiagnosed mental retardation.

- “Individuals seeking reproductive counseling who have

- A family history of fragile X syndrome or

- A family history of undiagnosed mental retardation.

- “Fetuses of known carrier mothers.

- “Affected individuals or their relatives in the context of a positive cytogenetic fragile X test result, who are seeking further counseling related to the risk of carrier status among themselves or their relatives.

- “Women who are experiencing reproductive or fertility problems associated with elevated follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, especially if they have

- A family history of premature ovarian failure,

- A family history of fragile X syndrome, or

- Male or female relatives with undiagnosed mental retardation.

- “Men and women who are experiencing late onset intention tremor and cerebellar ataxia of unknown origin, especially if they have

- A family history of movement disorders,

- A family history of fragile X syndrome, or

- Male or female relatives with undiagnosed mental retardation.”

ACMG does not recommend general population carrier screening.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published committee opinion 691 (ACOG, 2017) which recommends Fragile X premutation carrier screening for women with a family history of fragile X-related disorders or intellectual disability suggestive of fragile X syndrome and who are considering pregnancy or are currently pregnant.

If a woman has unexplained ovarian insufficiency or failure or an elevated follicle stimulating hormone level before age 40 years, fragile X carrier screening is recommended to determine whether she has an FMR1 premutation.

All identified individuals with intermediate results and carriers of a fragile X premutation or full mutation should be provided follow-up genetic counseling to discuss the risk to their offspring of inheriting an expanded full-mutation fragile X allele and to discuss fragile Xassociated disorders (premature ovarian insufficiency and fragile X tremor/ataxia syndrome).

Prenatal diagnostic testing for fragile X syndrome should be offered to known carriers of the fragile X premutation or full mutation

National Society of Genetic Counselors

The National Society of Genetic Counselors published guidelines which recommend: “Centers offering population screening should ensure that they have the resources available to provide pre- and post-test genetic counseling that supports the psychosocial and clinical needs of the patient and family. In light of widespread FMR1 testing among women without known risk factors, genetic counselors should anticipate seeing patients who did not receive any pre-test information, have no prior knowledge of FMR1-associated disorders, and are unprepared to learn that they have an FMR1 mutation.

Prenatal diagnosis should be offered to women with pre- or full mutations. Males with premutation alleles should receive genetic counseling about potential phenotypic risks to their daughters, all of whom will inherit premutations”(Finucane et al., 2012)American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Genetics

The American Academy of Pediatrics (Hersh & Saul, 2011) recommends testing for FXS in children with any of the following, particularly when associated with physical and behavioral characteristics of FXS or a relative with undiagnosed intellectual disability: Developmental delay, Borderline intellectual abilities or intellectual disability, Diagnosis of autism without a specific etiology.

Billing/Coding/Physician Documentation Information

This policy may apply to the following codes. Inclusion of a code in this section does not guarantee that it will be reimbursed. For further information on reimbursement guidelines, please see Administrative Policies on the Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina web site at www.bcbsnc.com. They are listed in the Category Search on the Medical Policy search page.

Applicable service codes: 81243, 81244, 81470, 81471

| Code Number | PA Required | PA Not Required | Not Covered |

|---|---|---|---|

| 81243 | X | ||

| 81244 | X | ||

| 81470 | X | ||

| 81471 | X |

Scientific Background and Reference Sources

ACOG. (2017). Committee Opinion No. 691: Carrier Screening for Genetic Conditions. Obstet Gynecol, 129(3), e41-e55. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000001952

Cleveland Clinic, Fragile X Syndrome and FMR1- Associated Disorders, Accessed Oct 2016.

Finucane, B., Abrams, L., Cronister, A., Archibald, A. D., Bennett, R. L., & McConkie-Rosell, A. (2012). Genetic counseling and testing for FMR1 gene mutations: practice guidelines of the national society of genetic counselors. J Genet Couns, 21(6), 752-760. doi:10.1007/s10897-012- 9524-8

Goncalves, T. F., dos Santos, J. M., Goncalves, A. P., Tassone, F., Mendoza-Morales, G., Ribeiro, M. G., Santos-Reboucas, C. B. (2016). Finding FMR1 mosaicism in Fragile X syndrome. Expert Rev Mol Diagn, 16(4), 501-507. doi:10.1586/14737159.2016.1135739

GHR Genetic Home Reference Fragile X syndrome, U.S. Library of Medicine, NIH, Accessed Oct 2016.

Hersh, J. H., & Saul, R. A. (2011). Health supervision for children with fragile X syndrome. Pediatrics, 127(5), 994-1006. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3500

Kronquist KE, Sherman SL, Spector EB. “Clinical significance of tri-nucleotide repeats in Fragile X testing: a clarification of American College of Medical Genetics guidelines,” Genet Med 2008; 10:845–847.

Miles JH. “Autism spectrum disorders—A genetics review,” Genet Med. Volume 13, Number 4, April 2011, 278-294.

Monaghan K, Lyon Elaine, Spector Elaine, ACMG STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES, Genetics in Medicine, 2013:15(7):575-586.

Saul RA, and Tarleton JC. “FMR1-Related Disorders,” GeneReviews. 26 April, 2012 Initial Posting: June 16, 1998; Last Revision: April 26, 2012.

Schaefer GB, and Mendelsohn NJ, for the Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee. “Clinical genetics evaluation in identifying the etiology of autism spectrum disorders: 2013 guideline revisions,” Genet Med 2013, 15:5:399-407.

Sherman S, Pletcher BA, and Driscoll DA. “Fragile X syndrome: Diagnostic and carrier testing,” Genet Med 2005, 7:8:584-587.

Spector EB, Kronquist KE. Fragile X: technical standards and guidelines. ACMG standards and guidelines for clinical genetics laboratories. 2005.

Sutherland GR. Fragile sites on human chromosomes: demonstration of their dependence on the type of tissue culture medium. Science. 1977; 197 (4300):265-6.

Verkerk AJ, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Fu YH, Kuhl DP, Pizzuti A, Reiner O, Richards S, Victoria MF, Zhang FP, et al. Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 1991 May 31; 65 (5):905-14.

Policy Implementation/Update Information

1/1/2019 BCBSNC will provide coverage for genetic testing for FMR1 mutations when it is determined to be medically necessary because criteria and guidelines are met. Medical Director review 1/1/2019. (jd)

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability in its health programs and activities. Learn more about our non-discrimination policy and no-cost services available to you.

Information in other languages: Español 中文 Tiếng Việt 한국어 Français العَرَبِيَّة Hmoob ру́сский Tagalog ગુજરાતી ភាសាខ្មែរ Deutsch हिन्दी ລາວ 日本語

© 2026 Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina. ®, SM Marks of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, an association of independent Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans. All other marks and names are property of their respective owners. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina is an independent licensee of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association.